Three figures stand on a clearing, their gaze directed toward the viewer or voyeur who either holds the camera, their finger on the trigger this very second, or who looks at the developed picture, maybe decades later, when it’s found in a dark and dusty attic filled with boxes full of pictures holding the story of a lifetime.

The figures seem to be standing on a path that leads into the distance. Have they walked this path before? The paradox of the footprint— “Lines are both created by being followed and are followed by being created.” A MOUNTAIN is towering in the background, overgrown with a coniferous forest and a few rectangular marks, possibly houses indicating human life. We hear a dark droning in the distance, a lonely alphorn player maybe or the SECRET SOUND OF THE ROCKS. It’s present at all time as we look at the image.

Three figures stand on a clearing. Behind them a valley full of stories that we never learn. Whether all of this is real life, or part of a miniature-landscape, we don’t know. The figure on the left is wearing straight, dark pants and a brown jacket. They carry a cane and a backpack asserting authority—or weakness. In any case we are inclined to believe them to be male. What does the backpack contain? What does it conceal?

Three figures stand on a clearing. Two of them are dressed as girls. It could be they are female, or it could be a disguise, a girl-costume to cover up whatever it is they need to hide, pleated blue skirts, yellow shirts and a short hair wig—the same character impersonated by different actors. Or, they are twins or clones. Or more likely one of them a doppelgänger demon: a spirit double, living another version of this life in a different dimension. But where they come from they’re not following a line, they’re clearing a path with a machete to explore the no-man’s land that they call home. Because they already know, what we still need to learn. And yet their strength, the will to walk an unknown line, is fueled by memories of girlhood that aren’t theirs, but lived experience of the other. Slingshot into one another’s universe they’re both doomed to haunt their lookalike forever.

Behind them, a second horn begins to play. They are now surrounded by a polyphonic hum.

Three figures stand on a clearing. It is unclear whether they met accidentally or if they knew each other from before. The path they are standing on, and that they are not walking at the moment, melts into the horizon. Together with the edge of the forest and the mountain it describes one eerie line, that tears through the image, dominating the interpretation as well as the two doppelgängers lives.

While we focus on the line, the HIDDEN IMAGE appears, revealing the “imagined thing called ‘THE FAMILY’,” carefully positioned between past and future. It raises the question: WHO IS TAKING THE PICTURE? A passerby, another father—or the mother?

The line is directed downward—a bad omen, no doubt. The girl-actor or demon on the right is oriented differently than the others. Their rounded shoulders and low chin indicate dissatisfaction. Are they rebelling? Or have they given up? On looking closer you clearly see that neither of the figures have human eyes, but hollow holes filled with a shadow. Are they POSSESSED? Are they all demons on a hike? Does the person taking the picture know?

Three figures stand on a clearing, one male, most likely, and two actors dressed as girls. They are directed by THE MOTHER that we cannot see. Is she secretly pulling the strings? Or is it not even a secret? The girl-impersonators vanish into the background as though they are slowly digested by the landscape. Either their life energy is being sucked out by the mountain, which clearly symbolizes a higher entity, or they suffer a rare condition, reverse-camouflage, in which they take the shape of their surroundings but not as a mechanism of defense but as a mechanism of surrender. The translucency might also be an indicator that they are a mere projection—but of what?

Or: The dissolving self is a feminist masterpiece, an expression of radical passivity . As we unravel this thought a slow, dark drumming adds into the tune. We realize: It is not the demon who possesses the girls, but the girls possess the demon. For the girls have a body but they have no will, and in possessing what they cannot have they refuse to concede. The demonic spirit stimulates outrageous desires that neither the mountain nor the father nor the mother can comply. Their bodies standing on the line unwillingly, not walking, undoubtedly are a demonstration of revolt. It becomes clear that their passivity is but a performance of masochistic fantasies, their stillness amplified into the throbbing buzz that echoes through the hills. It will liberate the memory decades later, consolidate body and spirit, and make this image a foreboding of the future.

The line will not be continued, the mountain will crash under its own weight, taking down the path, the forest, the houses and all life with it, mother and father will unremember, the demon-daughters will pass on nothing, this moment will be completely forgotten and whatever comes after will start anew.

The finger releases the trigger. The shutter shuts and reopens. A cloud passes the mountain and the droning fades out.

My mother, her sister and their parents continue the hike.

Years later my brother finds this picture in a box full of pictures and sends it to me. As I see these figures stand on the clearing, the droning begins to rattle my brain as it rattled the mountain that day. And in “THE MOMENT OF TRUTH WHEN THE MIRROR / REVEALS THE ENEMY” I know that all along the demon, the girls, the father, the mother, the alphorn player, the mountain and the path have been enmeshed into the very fiber that is I.

I was reminded of this last year when I visited East Sooke regionalpark on Vancouver Island in Canada, together with my partner.

Preparing a hike through the park we learned that there are black bears living in the forest and that the best way of interacting with them is to not interact with them at all. Meaning to try and go out of their way. Bears, and in specific the small black bears are rather shy. They usually avoid humans and are hardly ever aggressive toward them. But to make sure that we would not accidentally stumble upon one, it was recommended to continually produce sound while walking through the forest. Be it through chatter, singing or even just through clacking sticks against each other. So from the beginning to the end of our hike, we created a soundscape of sorts.

It was an overwhelming day for me. The hike was my first encounter with an old growth forest and East Sooke is beyond any nature I had ever seen. Despite the hiking trails that tore through the forest and the occasinal signpost, it seemed like a truly wild place to me. Or the closest that I ever got to being in the wild. We met only two other hikers throughout the whole day and we also did not encounter a bear—or any other creature larger than a bird for that matter. And even though I was glad to not face a bear I began to wonder whether it was my place at all to try and scare them away. Was this not their territory rather than mine?

That hike became the starting point for this project. Despite the beauty and serenity I experienced, the day also made me think about how detached I feel from whatever it is I mean when I talk about nature. Walking through the forest with admiration is far from being part of the forest. Even more, the admiration only adds to the divide of nature and culture.

However, I did feel kinship with the creatures that I did not see that day.

I am familiar with trying to be invisible, it might come with being a woman, identifying as queer or being raised in a traditional nuclear family with a dominant father and a quiet mother. Not showing myself—even in my own „territory“—has always felt necessary and thus natural to me. My own marveling gaze reminded me of the sexualized gaze that I am so used to receiving—replacing empathy with affection and respect with admiration. “We have evolved as talkers and dreamers.“ says nature-writer Richard Mabey. “That is our niche in the world, something we can’t undo. But can’t we see those very skills as our way back, rather than the cause of our exile?”[1]

I started to wonder what this thing was, that lays between me and nature and between nature and culture—this thing that we have no word for. Could talking and dreaming become a way of filling that void, a gateway to reconnect with other beings? Should I try and add my particular ‘singing’, as Mabey puts it, to that of the rest of the natural world? Stories are how we direct ourselves, allowing us to be in the world—or to speak with Donna Haraway, who cannot be unnamed in this, to be “with the world“.[2] Instead of making a soundscape to scare the creatures away, could I make a soundscape that would engage with them?

My particular singing

“We may want to forget family and forget lineage and forget tradition in order to start from a new place, not the place where the old engenders the new, where the old makes a place for the new, but where the new begins afresh, unfettered by memory, tradition, and usable pasts.” [3]

Investigating the kinship that I felt with the forest-creatures strangely takes me away from the forest, initiating a research into my own past and family history. I grew up in the countryside. Animals, trees and and the vast agricultural landscape of the Rhineland had been an important part of my upbringing. But the more I investigate my early relationship with it, the more uncomfortable I feel. In my memory my childhood and early youth were shaped by being outside, running, digging, sweating, tearing clothes, bruising knees, falling off of trees, slipping in animal shit and covering myself in earth and dirt and sand and mud. But all the photographs I can find of myself portray a clean girl with braided hair in a cute outfit. Am I delusional? Or are these pictures presenting a fake version of me?

Many of these images were taken by my mother’s mother. I remember she would bring me and my sister the same dress in different sizes whenever she came to visit. We would look like one tall, one short version of the same girl, wearing a yellow dress with a flower print and braided pigtails. She used to take her camera with—almost everywhere. Throughout her life she build an extensive archive of: flowers, leaves, mushrooms, trees, roots, sticks, stones, feathers, rivers, lakes, bees, frogs, birds, moths, snow, rain, drips—and of us.

Looking back at this it seems to me that she was fixated on two things: On nature and on girlhood.

She did not allow us—or my mother and her sister before us—to behave ‘unbecoming’. My mother tells me, that we would change completely when we were in her presence: We would become quiet and timid and brav.

We knew our mother had a violent childhood, despite never really understanding what had happened. She would complain about her mother when she was alone with us, but she too would become silent when her mother was around. We felt that she was still scared—or maybe we only felt our own fear through her. Therefore whenever she would ask us to be nice, to wear those dresses and smile, we would conform.

Recently I came across photographs that my grandmother had taken of my mother and her sister when they were children. One in particular stood out to me: It shows my mother, her sister and their father standing on a clearing in front of a mountain. The girls too are dressed in the same clothes. And what‘s more, they are blending into the background as though they are part of the landscape, part of the mise-en-scene, completely deprived of their individuality.

This seemed like the perfect narrative for my research. I asked my mother if she could find me one of those pictures my grandmother had taken of my sister and me, wearing the same dress that she had brought us.

My mother was surprised. She told me it was her who had bought the same dresses, not my grandmother.

Now I can‘t help but wonder: Am I trapped in a loop? Did this girl who I thought I was ever exist? Have I been clacking sticks all those years to scare away whatever I thought I needed to hide.

“For women and queer people, forgetfulness can be a useful tool for jamming the smooth operations of the normal and the ordnary“ writes Jack Halberstam. Instead of continuing the lineage of being dressed as a good girl and dressing the next generation as good girls too, can I forget how to be a good girl, a girl alltogether, and become a girl-creature or just a creature and not a girl anymore at all.

I am thinking: What if the kid covered in shit and the black bears from East Sooke exist in the same space? What if they are in hiding together? What does their hiding place look like? How did they manage to remain unseen for so long? It must be a place in the dark, underneath the surface, a place where no one ever looks, a place where creatures from different places come together and live side by side, maybe even in a space in a different dimension and in a different time. Looking back there is only one site to which this applies: my memory of our family pond.

“The pond lies like some mute oracle at the juncture of the human and non-human world, prodigiously deep and blank-faced”, writes Mabey. [4] I think this might be where we are.

Clacking sticks is told around the fictional triad of house, pond and forest. The pond lies between nature and culture, but it also symbolises the queer, all that is weird, the melange of shapeshifting creatures as well as bears and girls and muddy kids. It’s a think-pond, but also a place to forget, to lie around, a place to have no purpose. What happens in the pond, stays in the pond. The house stands for the domestic, the will to control nature and its beings as well as the wish to control girlhood. And the forest lastly stands for the idealisation of nature, a romantic idea of pristine nature as well as a fixation on pure, ideal girlhood. From the house you cannot see the pond, you can only see the forest.

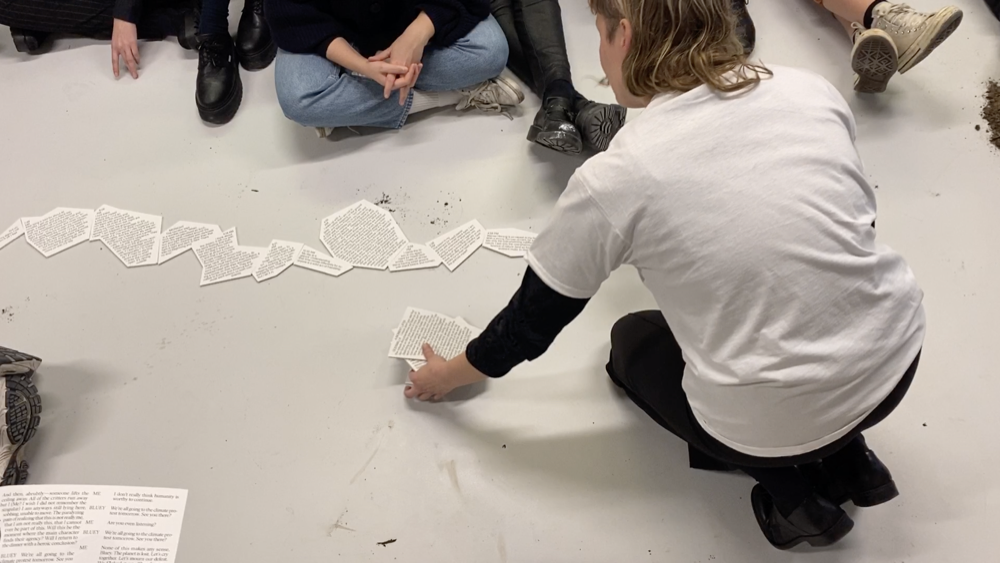

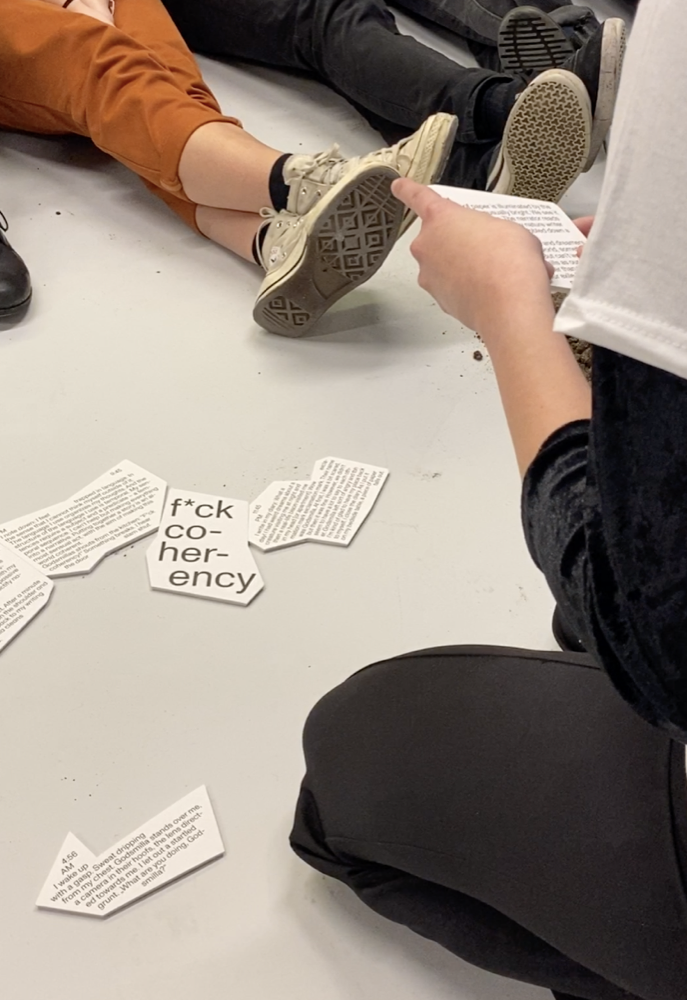

A live experience

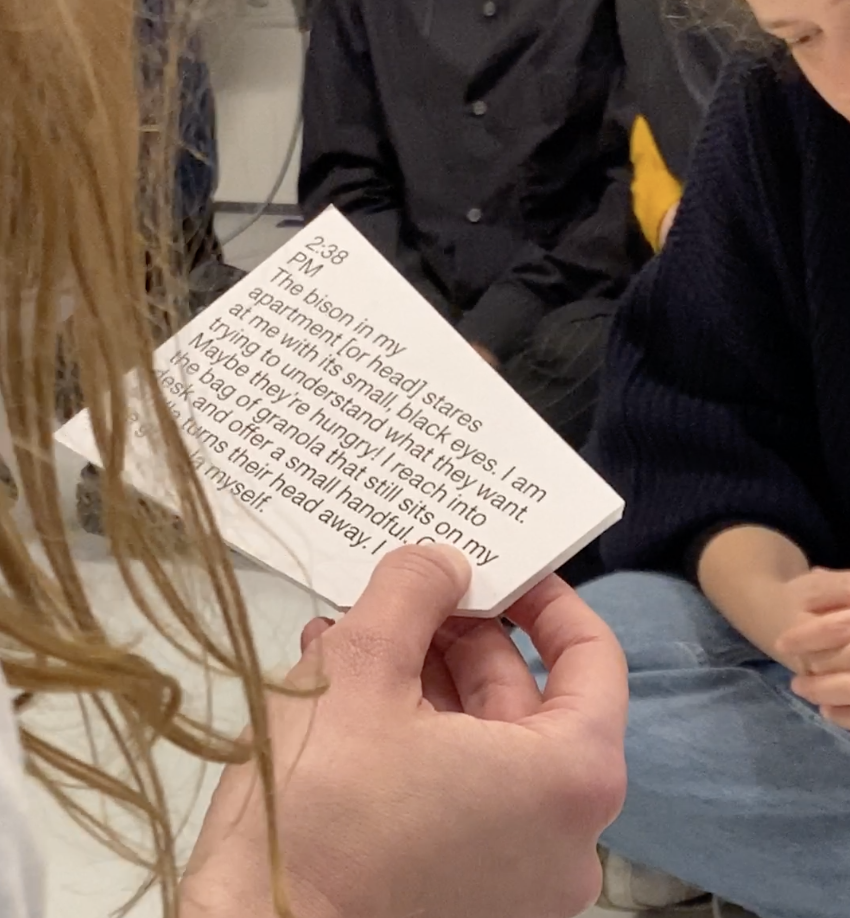

At the core of my performance is a reading of the manifold stories of the house, the pond and the forest that I am continuously writing. Additionally I am creating soundscapes that I use as the score for my performance. I started a growing library of sounds that I record in all possible spaces. There are field-recordings, voice-recordings and instruments, that probably were never meant to be instruments at all—like gloves or magnetic tape. These soundscapes are never just a reproduction of nature. They are half recorded, half generated and then reassembled. I am trying to find a soundscape of the in-between nature and culture, essentially the soundscape of the pond. The text I am working on is a repository of stories. My writing is nonlinear, associative and layered, representing the experience of an ever repeating generational trauma and the claustrophobia of femininity. This allows me to pick moments of the narrative and transform them into performances, always considering the circumstance, the time and place in which I am performing.

In the next months I would like to add another dimension to my work and build the pond that is at the core of my story. For this I don’t want to build an actual pond, but an approximation to what I think the pond could be. Similar to my previous performance Making of a forest, in which we used fabric, projection, scents and a forest soundscape produced by the audience using instruments that we provided, I would like to create a fictional pond as a spatial framework. The pond then becomes the place for me to read, but also a space for the audience to dwell in, to listen and to interact with the performance itself.

Like in my writing and recorded work it will be important not to try and replicate nature. I want to create a translation of the natural world into other materials and means and build an ephemeral and immersive experience that describes precisely something other than nature: the divide I felt that day when I was hiking at East Sooke.

[1] Richard Mabey, Nature Cure, P. 37 [2] Donna Haraway, Staying with the trouble [3] Jack Halberstam, the queer art of failure, p. 70 [4] Richard Mabey, Nature Cure, P. 227

“I think that we are sort of entrapped into this framework. One size fits all. When really all of this, coming home late, pitching for Nike, a flat with two bathrooms, craft drinking vinegar — it has nothing to do with the fibres, the physical and emotional material, that we’re made off. States of emergency tend to narrow down our options. I admit there really isn’t much I can hold against saving the planet per se. But nature, as Isabel Waidner writes, seems to be in itself “middle- classed”. What if the world, as it is, already is uninhabitable for some of us, what if we’re not part of this narrative? Or what if, in fact, it has already ended for some of us? I am borrowing this thought from someone I met at a reading group — I don’t remember their name.

The planet — (THE PLANET? — what is that even supposed to mean?) This incredibly complex, lawless, anarchic entity that does not fit into my head — it doesn’t need saving. Life will go on without us. So what we’re really talking about, is saving ourselves — and the feeble, little lives that we’re living. I too am caught up into this. I have nothing to offer but a childlike resistance to this story and thus in my resistance I reproduce what is already there. This very narrative that I’m putting together right now follows the guidelines of classic storytelling: at the beginning the main character, in this case I, feels trapped in a dissatisfying situation that they need to break free off. I am so entangled into it, I don’t notice it anymore.

So I will try to challenge my little brain and think something that resists to be thought.

When I was a kid, I learned that life was a perfect circle — like earth, looked at from space. From dust we come and to dust we shall return. I learned that the state of nature is harmony. The cat eats the bird eats the worm eats the leave and the leave produces the very air that we all breathe. Everything has its purpose and meaning.

But why then did I feel so displaced?

I felt like a creature inhabiting a human body all my life, like a parasite invading a host, controlling their brain. To what purpose? My movements weren’t mine, I was merely orchestrating, trying to copy what I saw: Keep head upright and back straight (not too much), roll left foot forward, heel-to-toe, when making a step. Move bodyweight forward, keep shoulders relaxed, bent right knee, move right foot forward and repeat process. Arms should swing naturally in small arcs. I hoped they wouldn’t notice that i‘m an imposter (but they did, and painfully so).

How I ached for all of this to stop.

I am longing for: A forest fire. Blazing its way through everything in its path. Breaking down years and years of growth and decades of continuity. Clearing out the clutter, the old and dead, making space for something else, opening the canopies to allow sunlight to reach the forest floor so that finally a more diverse vegetation can emerge.

I am longing for: The eruption of a volcano. Smothering everything in range and covering it in ashy grey. It will take centuries, but with time what was there will be replaced by something else, something unpredictable. An entirely new ecosystem.

I am longing for: A mutation. Erratic, spontaneous and random. Slowly propagating, subverting the established order.

I am longing for: A paradox. Holding two contradictory thoughts in my head at the same time.

I am longing to: Unknow this place. Never having been here. Not knowing my way around, not recognizing the landscape, not understanding the hierarchies, unestablishing any given order. Undo the harmony. Forget the names of things, unlearn the words to describe what I see, unlearn language altogether. Unsee day and night and twilight, untaste springwater, an apple, my own spit. I long to unlearn earth and myself in it.

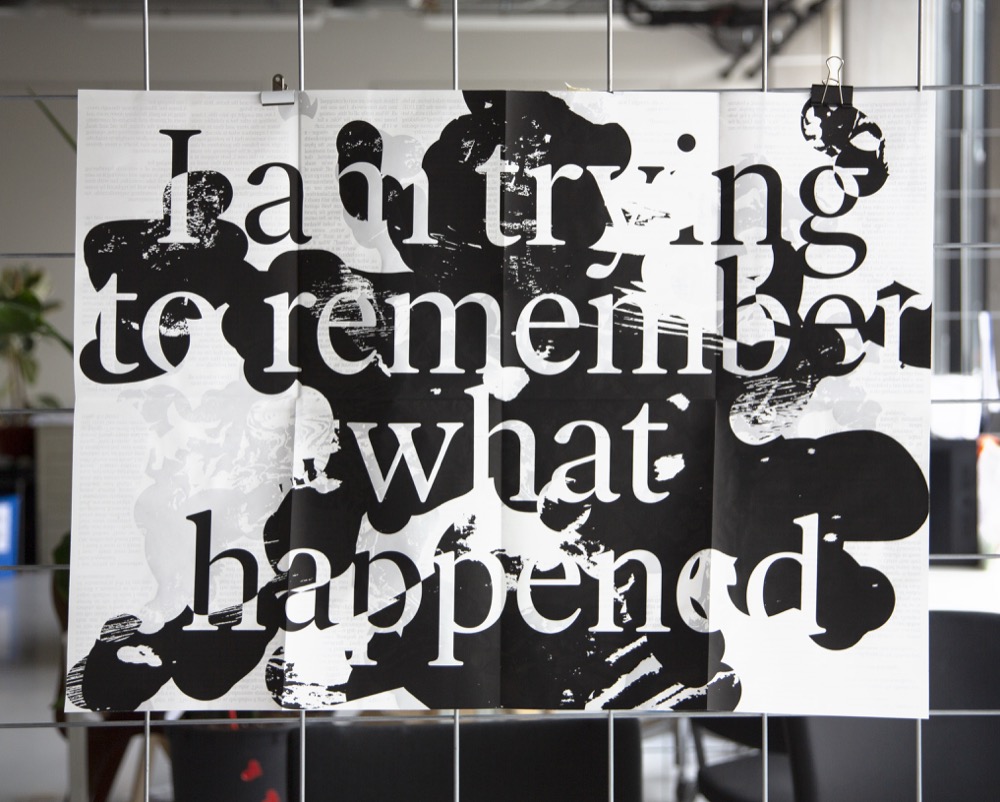

– – –And then I open my eyes for the first time, I blink, I am blended by the light, I don’t understand what’s happening and how i got here. Three Screens light up. Morphing images appear of leafy green. Of a forest, but it bears a strangeness. The sound of something like an echo of a windy night. Trunks softly dancing maybe in a breeze. Or maybe they’re actually just dancing. Quietly alive in chaos, moving unlike any forest would, alien yet soothing. Everything is resonating nature, but it’s not quite real. Like a memory of nature, or like the images that are projected on the inside of your eyelids, after a long day spend in the forest, the vague shadow of what I used to call a memory in the back of whatever is left of my consciousness now.

I am trying to remember what happened. I was… there were trees ... I think I went to a forest. Old, unlike any forest I had seen before. Trees so high and wide — they have seen centuries. Ferns were covering the ground. It was not dark, nor was it bright. I remember shapes of green. Lavish greens, brilliant and bright or dark and murky covering rock and earth and fallen wood. Trunks covered with lichen and moss. I remember the air. Misty, grey. A moistness lies over everything: Wet humus, soggy leaves. Damp earth and fallen foliage. The smell of pine and resin lies over everything. It’s heavy.

The farther I walk in, the darker it gets, the more I remember. Mushrooms appear in different shapes and shades. They must know I’m coming. They’re poking out their heads right before I see them, unfolding their caps to catch my glance. I pick one in passing from a trunk. It’s small and brown and smells like all mushrooms do: earthy and a little sweet and welcoming. I put it on my tongue to get a taste and without thinking, I gulp it down. I swallow it whole, without chewing so as not to destroy the little thing.

Hours later I am still on the path. A dusky ambivalence has settled over me. The path starts melting into the shrub, into the trees and finally the beat of my foot on the path and the shrub around it and the trees on top of me start melting into my breathing. I am concentrating on the slow rhythms of the forest: ONE—the rustling of branches—TWO—a breaking twig—THREE—trunks gnarling in the wind—FOUR—a flap behind a bush—ONE—the rustling of branches—TWO—a breaking twig — THREE — trunks gnarling in the wind—FOUR —a flap behind a bush—ONE —the rustling of branches— TWO — a breaking twig—THREE — trunks gnarling in the wind — FOUR — a flap behind a bush—ONE—the rustling of branches—TWO—a breaking twig—THREE —trunks gnarling in the wind —FOUR —a flap behind a bush—

I notice how my last thoughts gather into little drops of water on the inside of my head, hanging off of the linings of my brain for a while, softly rocking with my every step — and then finally evaporating into darkness. It is now pitch black.

[...]